Local warming

The climate history of our spaces

Notes from the Inflection Point explores climate grief, action, and adaptation. In a voice dedicated to seeing things afresh, again, and with agency, we offer readers reflections most Thursdays.

Seattle’s climate history is recorded in its lack of AC.

Air conditioning is a relatively rare amenity in Seattle. You might find it in ritzy tech campuses, luxury apartments, or recently remodeled museums. Some renters and homeowners have AC units, or even central air, but plenty more do not, especially south of the shipping canal. You won’t find it on college campuses, not even upscale private schools. You won’t find it in government buildings, libraries, or community centers, unless they’ve been remodeled recently in order to double as emergency cooling shelters.

Instead, you’ll find dense, well-insulated brick buildings constructed like ovens, with windows that rarely provide enough of a cross-breeze to replace the air more quickly than it heats up. In their defense, these buildings are great at being warm in the winter. When I first moved to Seattle, I worked in a typical university lab: in a brick-walled building with an AC unit that was perpetually broken. My labmates and I broke all reasonable lab dress codes and still sweated as we worked.

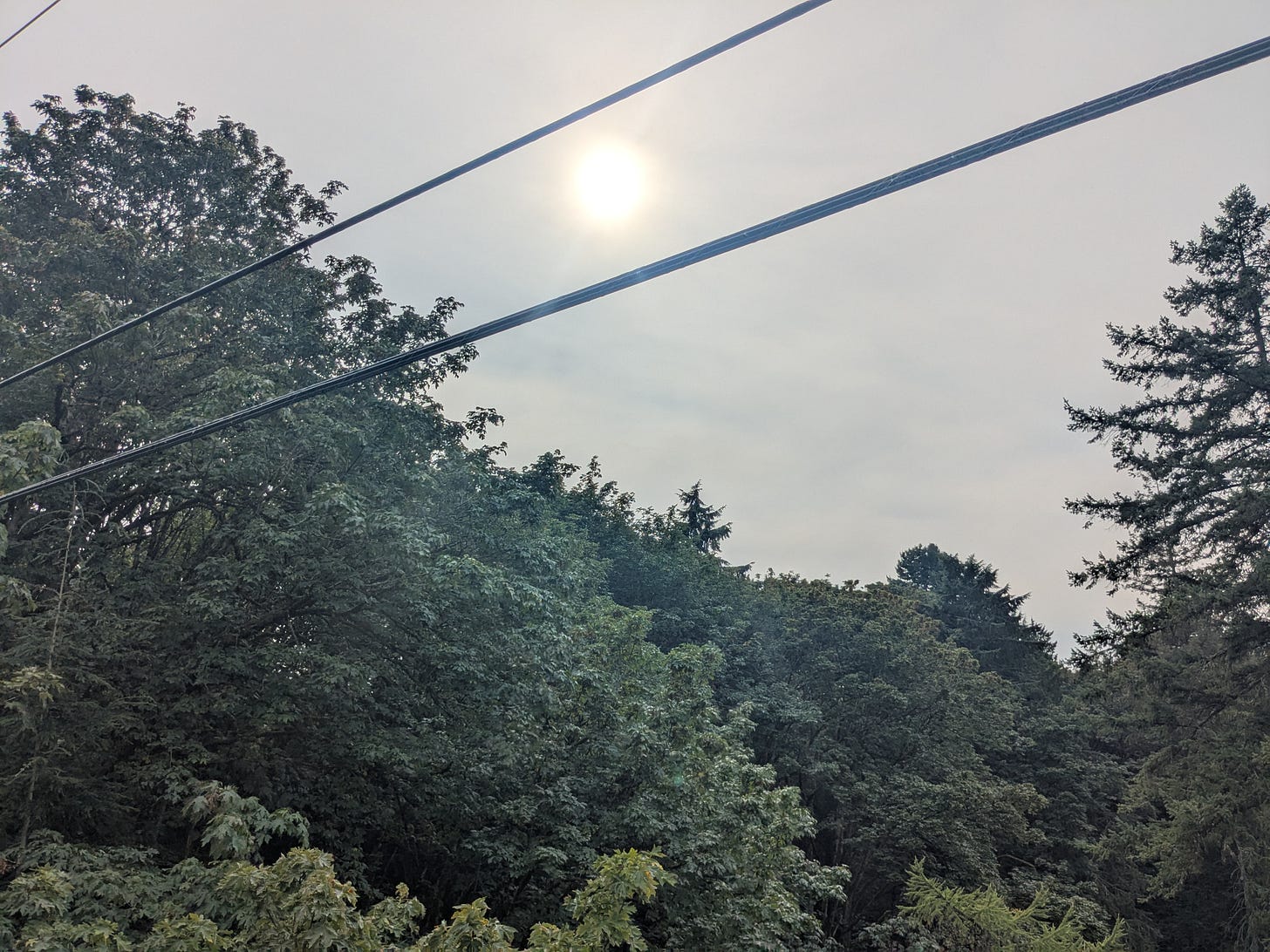

To make things worse, as the summer stetches out, smoke curls around the city from wildfires that were shocking a decade ago.

Just yesterday, the AQI shot up from 41 to almost 150 in the span of a couple hours: the atmosphere turned over and brought down high-level smoke from fires burning in British Columbia. The air smelled like campfire, permanent marker, and burnt plastic. The pervasive brown haze was visible just looking down the street; I could barely see the city skyline across our small Lake Union. The sun was blocked out in a yellow-white sky. In these conditions, you can’t even open your windows.

I’ve lived in Seattle for just four years. I’ve been told that it used to be cool enough here that buildings didn’t need AC. Average summer temperatures in Seattle supposedly topped out at the mid-70’s, and it still rained sometimes. Every summer I’ve been here, though, the region has been mired in deep drought: virtually no rain, or even clouds, between July and September. To me, it feels normal, like Seattle must have always been this way.

How will we live through hot summers into the future? How will we protect our neighbors and community members through extreme heat and smoke?

I know the techniques for keeping living spaces cool without AC: open the windows overnight, close the blinds during the day, mount cardboard or Mylar over the glass to block the sun. Drink water, strip down, don’t turn the oven or stove on more than you absolutely need to, don’t move too much. Go to an air-conditioned building or a beach, if they’re open.

This advice is more possible to follow for some than others. I’m fortunate: I have masks and air purifiers. I live in a basement-level apartment, so even without air conditioning, I can keep the windows closed and stay cool enough. On upper-floor apartments unshaded by trees, and in the urban heat bubbles created by blocks and blocks of concrete and asphalt, living space temperatures rise to 80, 90, 100 degrees or more.

Three weeks after I arrived, the region experienced a “heat dome”: a week-long stretch of extreme heat with temperatures in the 90’s and 100’s. I found this range unremarkable at the time, having just moved from the Midwest where summer temperatures were regularly that high. However, Seattle does not have the infrastructure to handle that level of heat. Over a hundred people died, possibly many more, most of whom did not have air conditioning or were elderly, chronically ill, or unhoused.

It has become increasingly unhealthy to live in uncooled spaces. Research has shown that when people are exposed to high overnight temperatures, they “are unable to cool down and recover from the daytime heat”, which can increase their risk of heat-related illness during the day (Environmental Health Perspectives, July 2023).

The twist of the knife is that air-conditioning individual spaces makes climate change worse. It weakens communities by isolating individuals. It feels like we’re on the other side of this particular inflection point: air conditioning is part of a feedback loop that drives summers hotter every year.

We can collectively advocate for community cooling centers, urban tree cover, energy-efficient infrastructure and public transit, and systemic support for those living outdoors. We can check on our neighbors who are exposed to the heat.

In a season that becomes more hostile every year, we can make the choice to live through it together.

Lou Baker (they/them) is a scientist and organizer. They hold a PhD in Aerospace Engineering and studied how wind and water currents carry microplastics in different environments. They now organize workers in higher education.